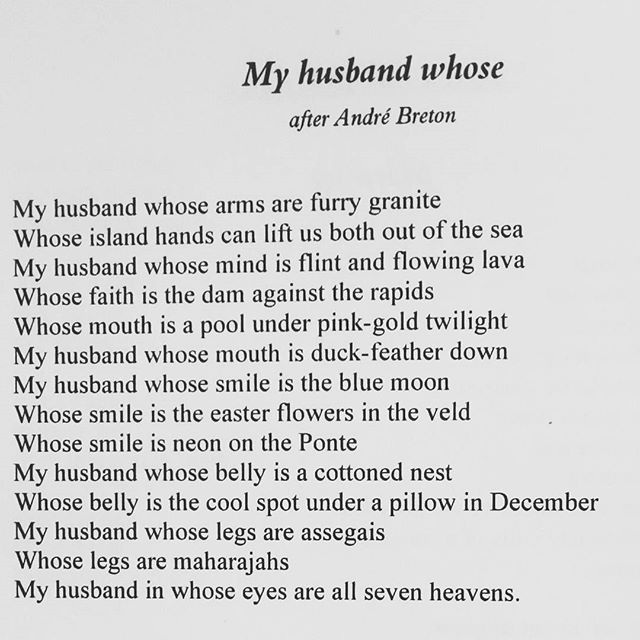

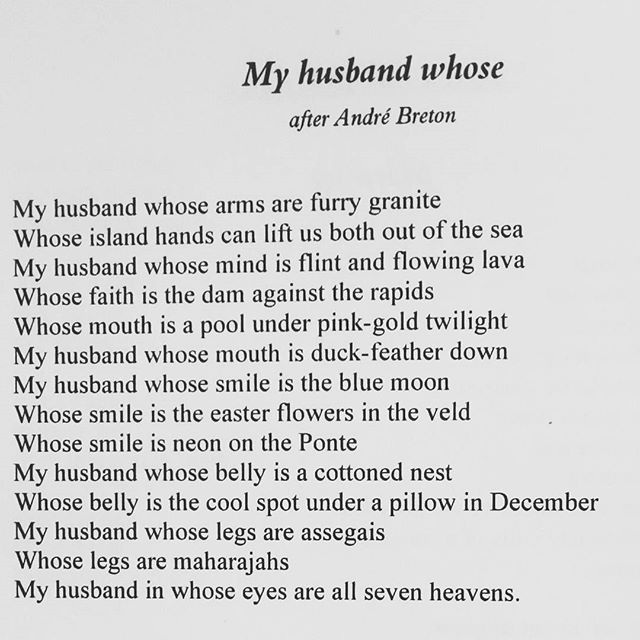

Growing bones’. Saaleha Bamjee, Poetry Potion. Issue 04. p.21. 2012

Author: saaleha

The Sunday Poem November 29, 2015 at 09:29PM

The Sunday Poem: October 25, 2015

Fiction Friday: Three Tellings

While editing older writings, I came across this narrative exercise from my MA coursework. For this assignment we had to take a scenario/vignette and write it in three ways, altering tense and POV in each.

I found that changing focalisations significantly altered the narrative for me, in an invigorating way. The next time you’ve stubbed your head against a writing block, consider switching your POV to one you wouldn’t ordinarily use.

Young Blood

Aunty Usha tells my granny she has seen Parvez kiss Marufah over the fence.

“Ja Haunty, you know, I see them. I see Marufah and that boy. I see her go upstairs to the flat too. It is not good Haunty, it is not good.”

Aunty Usha lives in the garden cottage in the house behind us. She speaks fluent Tamil, wears her false teeth only when eating and swaps most of her A’s for H’s.

Each of her visits to my grandmother is a showcase of arthritis, blood pressure and sugar; they put on their best aches while they swap hospital records and recipes for eucalyptus balms. Until this revelation, with flames licking at its seams, that our 15-year-old-next-door neighbour Marufah, and our twenty-something Pakistani tenant Parvez, are scandalising, by way of Parvez kissing Marufah’s hand, after she’s given him some sort of parcel over the pre-cast fence separating our properties.

And there is also the matter of Marufah gaining entrance to our backyard and going upstairs to the flat Parvez rents from my uncle.

My granny nods, shakes her head, and says, “You know young blood, Aunty, they can do anything.” It is shameful, they all agree, but who will tell Apa Fatima, Marufah’s mother; that formidable force, all hard voice and iron hand? Apa Fatima, who wears her practice of Islam like armour against all that is Western to her mind, whose family eats all their meals seated on the floor, who hosts weekly religious gatherings at her home and who commands the reverence of our community.

For a holy-moly like Marufah, the weight of black-cloaked modesty laid upon her well before she hit puberty, to be getting more action than I could ever write about in my diary, is incredible. And it is unimaginable that she would risk her mother’s wrath by carrying on with a Pakistani man.

But Aunty Usha has seen it, and she has no reason to lie.

After the visit, my granny tells my uncle to have a word with Parvez. No one sees Marufah in our backyard or close to our fence again.

Parvez moves out of the flat a few months after. He tells my uncle he needs a bigger place for when his wife and children arrive from Pakistan.

The man next door

Your mother gives you a Tupperware filled with some of the curry she cooked for supper.

She’s dressed to go out; a long black cloak obliterating her silhouette, her veil perched just above her forehead, ready to drop over her eyes as soon as she’s out the door. She clutches her car keys in one black-gloved hand and holds a thick file in the other. Every Thursday afternoon, she teaches ladies how to wash and prepare bodies for Muslim burial. Your mother tells you to give the curry to Aunty Mabel and to tell her that it is for that Pakistani man next door.

It’s not unusual for your mother to prepare extra meals for others. Beggars who come to your door leave with more than just bread and butter. Your heart is full of love for her and you feel guilty about the the anger you hold just below it. Your mother lives for Allah, and you are still finding your way to Him. You have questions for her but you can’t ask them.

You go out to find Aunty Mabel. She’s worked for your family since before you were born, and is more mother than your own sometimes. You can’t find her and you decide you will give the food to the Pakistani man yourself. You know your mother will be upset if she finds out. She doesn’t approve of you speaking to strange men, even when you are wearing your veil.

You wait just outside your kitchen door. It’s the closest to the gate he uses as an entrance. The wait is not long, you hear his keys. Your veil is in your room and if you go and fetch it, you will miss him. You stand on the flower pot and call out to him with your face exposed. He smiles up at you, a smile that stays in his green eyes. You are suddenly shuffling for words and you tell him that your mother cooked a little extra for him.

His English is just ever so slightly broken. It’s utterly charming. You are charmed. He asks you what your name is. His name is Parvez.

As you pass him the plastic container, your hands brush for a second. The contact is so minimal and yet you flush red. He is still smiling as he walks away.

You hear Aunty Mabel in the kitchen. You rush to tell her that you’ve given the food to Parvez and that she mustn’t tell your mother. Aunty Mabel is so used to indulging you and your siblings, she will lie for you again.

Over Fences

Usha’s sunflowers grew taller than the fence; their faces drooping slightly forward, full and magnificent. She liked to look at them. They reminded her of a time when she and her husband were tall, when they too were something to behold, long before osteoarthritis shrunk her and diabetes claimed his foot. It was during this meditation that she noticed Aunty Hawa’s tenant and the other neighbour’s daughter, Marufah , speaking over the fence.

She knew that those neighbours were very, very strict Muslims. The ones where the women only left their houses covered in those long black dresses and face veils. Not like Aunty Hawa, who was also Muslim but dressed in different colours. Usha knew that Marufah’s mother would not want her speaking to a man she wasn’t related to, especially Aunty Hawa’s handsome young Pakistani tenant. Marufah was laughing and Usha recognised the light in her eyes. The Pakistani had bewitched her.

She saw Marufah extend her hand to the man, who brought it up to his lips. “This is not good,” Usha thought. “Not good at all.” She picked up a broom and knocked it against the fence. She hoped the noise would be loud enough to alert the couple of her presence. It worked. They parted quickly and Usha went back to tending her sunflowers.

It was the next Thursday afternoon and Usha took her crocheting out into the garden. Their cottage didn’t get much natural light and she didn’t want to disturb her napping husband with the fluorescent casting over his bed and her busy needle. Her concentration was broken by the sound of someone climbing the stairs to Aunty Hawa’s tenant’s flat. She looked up, expecting to wave at the Pakistani who always greeted back. She saw Marufah instead, looking like she was concentrating on being invisible.

Usha’s gaze followed Marufah into the flat. “This is bad,” Usha thought. “I must tell Aunty Hawa about this, she won’t want this kind of thing to be carrying on right under her roof.” While the Pakistani was always kind and polite to Usha, she knew they had something of a bad reputation when it came to women. Her own grand-daughter got involved with a foreigner and was now expecting a child. They’d married but Usha was not happy with the union.

With her mind unsettled, Usha looked to her sunflowers.

The Sunday Poem: September 27, 2015

Camera Collectanea: Shine Strong High Tea, Beautiful Things and Paper Cameras

Good Housekeeping’s Pantene Shine Strong High Tea|27 August 2015

When an invite to Good Housekeeping’s Pantene Shine Strong High Tea dropped into my inbox, I cleared my schedule. I never pass on cake and a cuppa.

It wasn’t all carbs and crumbs at the lyrical Shepstone Gardens though. Proceeds from the the High Tea benefited Sisters4Sisters, a community-based non-profit who, among other aims, works towards empowering women in abusive situations. The event’s overarching theme was one of unapologetic strength. SA Fashion Week founder and director, Lucilla Booyzen welcomed us as confidants, sharing her story of a life designed by dreams and drive.

Lucilla Booyzen shares her unflinchingly honest life story. “I wanted to live my life without any secrets.” #GHShineStrong

— saaleha i bamjee (@saaleha) August 27, 2015

“It’s important that we as women see the potential in others…create those opportunities for them.” – Lucilla Booyzen. #GHShineStrong

— saaleha i bamjee (@saaleha) August 27, 2015

Unless I’m bound to by blood or emotional bondage, I unfollow people on Instagram who regularly post motivational masturbation and obvious life affirmations overlaid on bokeh backgrounds. Therefore, I’m not generally appreciative of inspirational woowoo, but listening to Booyzen, and the other speakers, I felt a current drill through me. Maybe it was the glycaemic load from the milktart cupcake I’d just inhaled. Maybe it was the realisation that I could in fact rewrite my life script anytime I wanted to. My take-home (along with the sexy Tupperware in the goodie bag) was the recognition that my own strengths lie in being resilient and re-inventive.

Coffee Worship

Camera-shaped Box with Moo MiniCard slot

I still receive queries about the Moo MiniCard holders I designed a few years ago. I don’t sell them but I have made the template freely available for anyone who wants to make their own (click here for that and more information). I’ve now taken the original design and adapted it to form a camera-shaped box large enough to fit a memory stick. It’s a fun and personable way for me to deliver work to ShootCake clients.

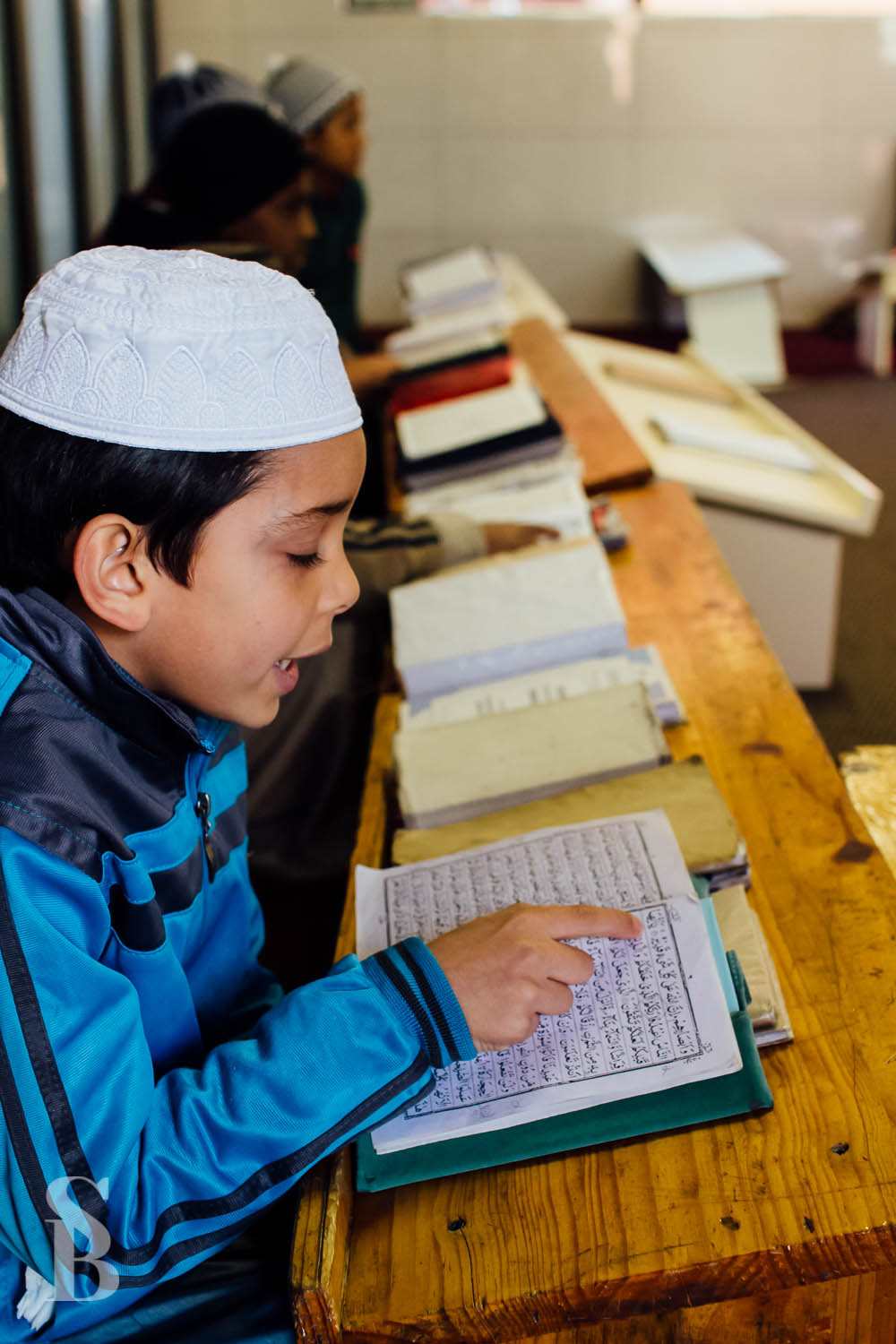

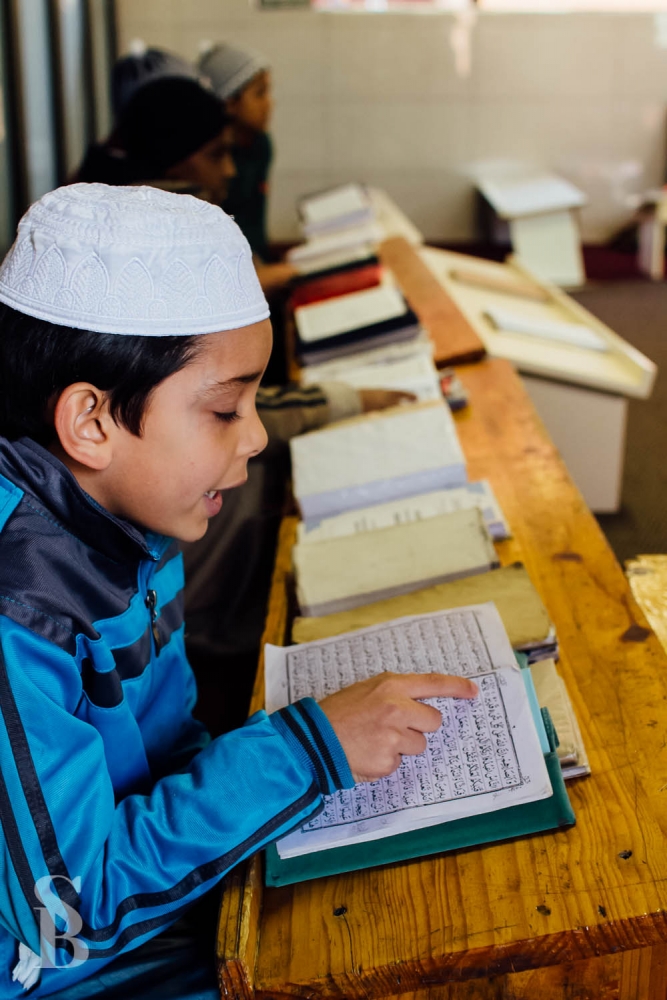

Madressah Zia-ul-Badr: Uplifting Young and Old

The malaise of areas within proximity of Johannesburg’s CBD is that they bear the preceding reputation of being crime-besieged. Visitors approach with a sense of caution, any business undertaken is scored by urgency.

However, in the eastern part of Jeppestown, in the historic suburb of Belgravia, that anxiety is quickly displaced. Should one take pause at the corner of Marshall and Kerk street, one will hear a singular chorus filtering through the gates of the neat building that houses Madressah Zia-ul-Badr (MZB). Verses from the Qur’aan, in multitudes of voices, rise up and out into the tree-lined streets. It is a sound that soothes even the non-Muslim neighbours says Qari Moosa Seedat, one of the madressah’s founders. “People’s perceptions are that this area is rough. This is not so. We are kilometres away from the hostels that were recently in the news regarding the xenophobic attacks. This area, old Belgravia where the mine managers used to live, is actually quite spiritual. All denominations have their presence here. There are also a number of schools in the area.”

MZB is a key addition to this suburb’s scholarly and spiritual legacy. The institute was established in 1988 with the aim of equipping those entering the fold of Islam, and those facing a myriad of socio-economic challenges, with a high standard of Islamic education. “This ensures that when they return to their communities, the result is the continual propagation of Islam,” says Qari Seedat. The Darul-Hifz complex, was officially opened in November of 2012 and includes a Masjid, student hostel, kitchen, dining hall and living quarters for staff and their families.

The student population is diverse, there are 16 African countries being represented, along with three students from the USA, who were sent to the madressah by their grandmother. “We’ve never traditionally advertised the Madressah,” says Qari Seedat. “Our applications come in via word of mouth. We often have students who are sent here by families who’ve already had other members come through our doors. You’ll find students who come from specific backgrounds or tribes. For instance we have a student who is now the fourth son in his family doing Hafizul Qur’aan here. They are originally from Mali, now based in Angola. Some of our students are orphans and some of them have the support of a family or tribal structure back home.”

There are currently 74 full-time live-in students, along with 19 who attend part-time. Seven of those are in their final year at the madressah. The youngest student is 7-years-old and is the son of the artist who painted a cheerful depiction of a seascape along one of the complex walls. “He used to accompany his father, a professional artist who lives in Secunda, to the madressah. The child does not have a mother and the father agreed to enrol him into classes.”

For most of the students at MZB, the madressah is the very beginning of their Qur’aanic journey. “We start from Alif Baa Taa all the way to the complete memorisation of the Qur’aan,”says Qari Seedat. Their instruction is comprehensively thorough, with students learning the individual alphabet of every verse they commit to memory. Considering the rigour of their study, a drop-off rate of 10-12 percent is exceptional. Over 80 Huffaaz have graduated to date. “That number increases to 120 if we include those students who were unable to return to the Madressah and who completed their Hafizul Qur’aan in their home countries,” says Qari Seedat.

Qur’aanic study at MZB is complemented by Tajweed, Hadeeth, Islamic History, Islamic Jurisprudence and Islamic Etiquette studies, along with English, Mathematics and Computer Literacy. “This ensures the holistic development of our students, many of whom go on to high school or further their Islamic studies at institutes like the Darul-Uloom Newcastle whose primary medium of education is English,” says Qari Seedat.

Along with the madressah, Qari Seedat oversees the running of the MZB Mothers Home, a new addition to the good work being undertaken at the complex. Launched in September last year, the home provides care for elderly Muslim woman who do not have sufficient family support. “We took our first mother in on December 1st. We now have nine living with us. Some have nobody left to look after them, some have been abandoned,” says Qari Seedat. The mothers live in a renovated heritage house that retains the classic stained glass and wood fixtures evocative of the comforts of home. In these spacious, light-filled surroundings, the women are given the care and attention they deserve, medically as well as psychologically. Every morning, they listen to Surah Yaaseen being recited by one of the hifz students in the home’s well-appointed garden. Visitors are always welcome and the mothers look forward to receiving them.

The home has the capacity to care for 25 mothers but are taking in applications gradually. The vision of the home was planted in the mind of Qari Seedat over 25 years ago when he was called to check on the well-being of an elderly Muslim lady who had not been seen or heard from for a few days by members of her community. “Her children lived overseas and she was all on her own, with no one to take care of her,” Qari Seedat says. He accompanied the police and fire department to the woman’s home and met with the grim sight of her decomposing remains. The incident weighed heavily on him over the years and he endeavoured to establish a place of care and safety for the elderly.

Establishing the home accrued substantial costs and MZB is hosting a fund-raising dinner on August 22nd at the Unisa Conference Centre in Ormonde to assist them in meeting those expenses. The dinner will feature Qari Ahsan Mohsin Mohammed Qasmi, one of India’s most talented Nasheed artists. The esteemed Qari is blind and is renowned for his recitation, attracting audiences of over 300 000 people when he performs.

Tickets can be purchased online at www.mzb.co.za

There will also be a number of masaajid programmes and the Qari will be hosted at WITS Great Hall, with the funds raised there benefiting the Bertrams Muslim Association and their madressah class project.

Click here to read Aaminah’s account of her visit to the madressah.

Notes to the Unconceived #3

Missives to the children I am yet to bear.

—

I don’t know what social media will be like when you’re old enough to set up your own profiles. I have a utopian vision of the entire infrastructure imploding, with only true and intimate connections surviving the fallout. I am not totally averse to the connected world that brought me your father and so many dear friends. It’s that as I get older, I crave the pure silence of the canyons and the wadis where the stillness is so thick and encompassing, one is able to hear all of time whisper to the soul. I try to seek out that silence by way of meditation; in washing dishes, in games of Freecell, in disconnecting from news feeds and online chatter. In that quiet, all my thinking expands and boomerangs. I find pause. I learn to listen.

You must always be able to hear yourself.

And when I do plug into the lives of others, I proffer the acknowledgements allowed for by the platform; liking, commenting, hearting, in all the ways we have to say, “Yes, you are here. I have noticed you in this crowd.” We share and we receive. We hear and we want to be heard. In that lies a trial. For with the beautiful and benign, there will also lurk the reptilian-minded urge to police each other, to want to dictate to others what they should believe and what they should care about. It’s seductive and when it’s done, you will feel like a giant tramping across the countryside, admiring the deep impressions created in your wake. But I’d rather you not be the kind of person who gets told, “ooh, looks like you were awarded all the tenders God issued when divine judgement was being outsourced.”

It’s important that you have strong opinions; about justice, mercy and the well-being of others. I pray that you are never gagged by fear, that you always speak straight from your heart. And when you do, I want you to ask yourself the following questions before you share that passion on social media;

Am I speaking from a place of sincerity? Have I really listened to myself?

What is the intention behind this update?

Am I posting this to further a cause or to influence the perception others have of me?

Will what I have to say effect change?

Am I adding anything new to the existing discourse?

Am I shouting into the crowd when I could be whispering into the ear of the person this is directed at?

Who will be affected by what I have to say?

Is there even the tiniest chance that my words will be received as being unfair or unkind?

If I were to step away from my device for an hour, and then return to it, will I still want to say this?

If these interrogations leave you uncertain, seek out the silence. Consider your place in the universe as a human being. Calculate the value of that opinion. Listen.